Over the past few weeks I’ve bene thinking about long takes.

Recently we were all amazed by ‘Victoria’ a movie that was staged as a single

tracking shot, we’ve seen this format before such as ‘Birdman’ of Alfred Hitchcock’s

‘Rope’, but never before as a genuine, start to finish, tracking shot that

doesn’t rely on any visual trickery to achieve this. It really is 138 minutes

of footage in an unbroken and continuous shot, all filmed exactly as it

appears.

So now that ‘Victoria’ has proven that a long take movie can

be accomplished should we expect to see a massive influx of them? In simple

terms, probably not. I expect to see some other indie filmmakers trying to

imitate the technique and maybe one or two major studious will use their

resources to try and push it even further, but if you’re expecting some kind of

revolution you may be disappointed.

It is linked to some of the inherent flaws of long takes. At

the end of the day is serves as a great way for a filmmaker to show off.

Hitchcock himself often referred to the use of tracking shots as a simple “stunt”.

In fact he always expressed a disdain for the finished product that was ‘Rope’.

The main thing that excluded from tracking shots if of course, editing. Editing

may be the purest way to tell a story, a la the Soviet montage theory. If you

use editing to flip from one image to another you find the audience subconsciously

drawing parallels between them. A classic example is Sergei Eisenstein’s ‘Strike’

that parallels the slaughter of a bull with the crushing of union strikers by

the government. Even more famously is ‘The Godfather’, as Francis Ford Coppola

cuts from Michael Corleone being baptised as a godfather to his sister’s new-born

child and being baptised as the new mafia godfather by eliminating the competition.

The parallels are endless, Michael is bathed in holy water in one image then

the blood of his enemies in the next, one sermon cleanses his soul and the

other cleanses the leadership of the mafia, just as Michael vows to renounce Satan

we see dozens of people being slaughtered in his name and on his orders. The

symbolic connections are established purely through editing, this is something

a long take simply could not do.

It is linked to some of the inherent flaws of long takes. At

the end of the day is serves as a great way for a filmmaker to show off.

Hitchcock himself often referred to the use of tracking shots as a simple “stunt”.

In fact he always expressed a disdain for the finished product that was ‘Rope’.

The main thing that excluded from tracking shots if of course, editing. Editing

may be the purest way to tell a story, a la the Soviet montage theory. If you

use editing to flip from one image to another you find the audience subconsciously

drawing parallels between them. A classic example is Sergei Eisenstein’s ‘Strike’

that parallels the slaughter of a bull with the crushing of union strikers by

the government. Even more famously is ‘The Godfather’, as Francis Ford Coppola

cuts from Michael Corleone being baptised as a godfather to his sister’s new-born

child and being baptised as the new mafia godfather by eliminating the competition.

The parallels are endless, Michael is bathed in holy water in one image then

the blood of his enemies in the next, one sermon cleanses his soul and the

other cleanses the leadership of the mafia, just as Michael vows to renounce Satan

we see dozens of people being slaughtered in his name and on his orders. The

symbolic connections are established purely through editing, this is something

a long take simply could not do.

At the same time editing can also be used to draw emphasis

to one aspect of a film, say for example you want to convey that one character

is lying or has something to hide, then the camera would pay specific attention

to his reactions and draw attention to his motifs. Or how about creating a

sense of tension? Then you would use your camera to quickly jump between each

aspect of the scene, emphasising a heightened sense of awareness and pace.

Tracking shots almost prohibit this, you have to search for

more creative ways with which to draw emphasis to any one specific aspect of

the scene. It’s also difficult to switch between formats such as close-ups or

wide shots and furthermore the camera has to manoeuvre around each element of

the scene rather than forego any obstacles through editing and reverting to

cutting between an action and a reaction. In essence, most tracking shots are employed

to convey large amounts of information on a visual level, not small and

intimate moments.

In fact ‘Touch of Evil’ may be an appropriate exception to

the tension rule. Welles manages to raise tension by starting the shot with the

panting of a bomb and shows it being carried away by a courier. We don’t know

the destination but the bomb frequently crosses paths with characters as they

are introduced throughout the shot making the viewer highly anticipative of the

end result. At the same time though ‘Touch of Evil’ also introduces the viewer

to an environment, which is something else long shots are great for. You can be

transported to the beaches of Dunkirk with the tracking shot of ‘Atonement’,

the glamour of a gangster lifestyle with the Copacabana shot from Scorsese’s ‘Goodfellas’

and then of course there’s the burning barn from ‘The Mirror’ as Andrei

Tarkovsky excels at environment building like no one else.

However these long takes all require scrupulous amounts of preparation

and frequently come about by accident. Martin Scorsese was forced to revert to

a long take when he wasn’t allowed to use the front entrance of the Copacabana

Club and instead moved his camera through the back entrance, corridors,

kitchens, storerooms and bypassed the queues of people in order to arrive at the

same destination. As for the beach scene in ‘Atonement’ while impressive it was

staged due to the budget not allowing director Jo Wright to hire all of the necessary

extras for a shoot lasting multiple days so he quickly carved out a path

through the beach and then sent the cameraman onto the back of a golf cart,

then on foot, up a ramp disguised as debris before reaching a rickshaw that

carried him the rest of the distance to finish the shot.

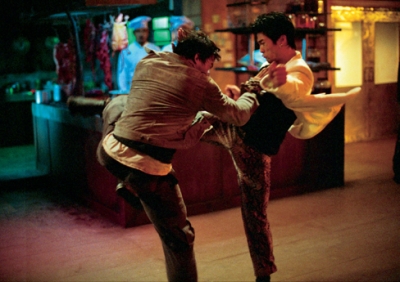

Few things look as amazing as a fight sequence performed as

a long take, but they also require a ridiculous amounts of preparation. Instead

of serving to minimise budget and time performing a scene in this style can

only increase both the former and the latter. In ‘The Protector’ Tony Jaa

fights his way up four flights of stairs in this scene and it took four days

and eight attempts to get the shot they were happy with, as well as having a

hire a completely new camera crew when the first couldn’t keep up with Jaa.

That’s a lot of effort for just four minutes’ worth of film. Then you have the

hospital shootout from ‘Hard Boiled’ in which the entire set had to be rebuilt

mid-way through the shoot. As two characters destroy one floor of the building they

enter an elevator and though we think they’re going up one floor, they’re actually

just waiting while the crew reassembles and redresses the same set for them to remerge.

Few things look as amazing as a fight sequence performed as

a long take, but they also require a ridiculous amounts of preparation. Instead

of serving to minimise budget and time performing a scene in this style can

only increase both the former and the latter. In ‘The Protector’ Tony Jaa

fights his way up four flights of stairs in this scene and it took four days

and eight attempts to get the shot they were happy with, as well as having a

hire a completely new camera crew when the first couldn’t keep up with Jaa.

That’s a lot of effort for just four minutes’ worth of film. Then you have the

hospital shootout from ‘Hard Boiled’ in which the entire set had to be rebuilt

mid-way through the shoot. As two characters destroy one floor of the building they

enter an elevator and though we think they’re going up one floor, they’re actually

just waiting while the crew reassembles and redresses the same set for them to remerge.

Not all directors have this much time and frankly not all of

them work well with the style. It takes a certain amount of choreography and an

intent upon what to move the camera towards what they want the audience to pay

attention to. The best tracking shots resemble directed chaos, while the worst

just look like chaos. But as I already said, this is much easier and sometimes more

effective with editing. Going back to Hitchcock, the ‘Psycho’ shower scene is a prime example in which

the editing is used to deceive the audience into thinking that they’ve just

seen something far more violent and sexual than what they really have.

When utilised appropriately long takes can be one of the

most spectacular things a filmmaker can do, but they are limited in their

storytelling ability, both visually and thematically. Providing a wider field

of vision for a viewer can have its advantages and disadvantages but ultimately

it all depends on what a director is trying to convey and the best method for

which to achieve it.

No comments:

Post a Comment